Lynchsong

By Lorraine

Hansberry

I

can hear Rosalee

See the eyes of Willie McGee

My mother told me about

Lynchings

My mother told me about

The dark nights

And dirt roads

And torch lights

And lynch robes

See the eyes of Willie McGee

My mother told me about

Lynchings

My mother told me about

The dark nights

And dirt roads

And torch lights

And lynch robes

The

faces of men

Laughing white

Faces of men

Dead in the night

sorrow night

and a

sorrow night

faces of men

Laughing white

Faces of men

Dead in the night

sorrow night

and a

sorrow night

1951

* * * * *

When McGee was taken to the courthouse to be tried, he was transported in a National Guard truck and dressed in fatigues to disguise his identity and protect him.

The night before McGee was electrocuted in 1951 by the state of Mississippi, he wrote a farewell letter to his wife Rosalie:

Tell the people the real reason they are going to take my life is to keep the Negro down.... They can't do this if you and the children keep on fighting. Never forget to tell them why they killed their daddy. I know you won't fail me. Tell the people to keep on fighting.

Your truly husband, Will McGee.

Bop: Ancient as Willie McGee

I was fifty then, casually delirious like migrants,

jumping fences, retro-style. I’d spent time with Milton

Eisenhower, brother of a president, who interred souls

needing repair, for a semester; slept with Queen Mary

for years in a second story room in northeast DC—

swore off black women to escape heart burning romance.

It no good to stay in a white man country too long.

Here is why. The tongue between blond-haired thighs

fills heads with Willie McGee news, flashing blue lights,

frantic in hand-me-down pants from he who whispers

cutting Polish jokes in the Taliaferro halls of humanities.

I rubbed bellies with virgins, daughters of early Tidewater

settlers. I studied French with a Dutch family housed along

the wooded Platinum Coast among ever-green ancient oaks,

a haven for nouveau riche fearless of rebellious blacks.

It no good to stay in a white man country too long.

I graduated with my mind staid on reaching heaven

in the Ituri forests of the Kongo, northwest of Bukavu

near Lake Kivu—my eyes netted silhouettes of Zairean

fishermen in morning mist, a tattered hull on a rippling rift,

ghosts of King Leopold, father of illegitimate sons, chopped

limbs; mercenaries murdering Lumumba on his knees, ad nauseam.

It no good to stay in a white man country too long.

Rudolph Lewis 10 May

2016

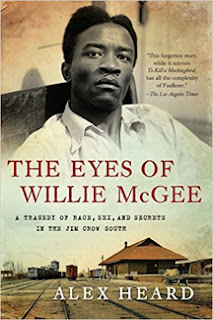

In this gripping saga of race and retribution, Alex Heard (editorial director of Outside magazine) tells a moving and unforgettable story of the deep South that says as much about Mississippi today as it does about the mysteries of the past. In doing so, he evokes the bitter conflicts between black and white, north and south in America

by Alex Heard

In this gripping saga of race and retribution, Alex Heard (editorial director of Outside magazine) tells a moving and unforgettable story of the deep South that says as much about Mississippi today as it does about the mysteries of the past. In doing so, he evokes the bitter conflicts between black and white, north and south in America

No comments:

Post a Comment